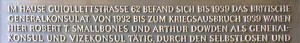

One of the few foreign diplomats, who concerned himself with the situation of those already being persecuted in November 1938, was the British consul general Robert T. Smallbones, who had been in his position in Frankfurt since 1932.

During a short visit in London in November 1938 he received shocking news about the destruction of Jewish businesses, the arrest of Jewish men and their helpless families as well as their frightened wives and children. He held meetings with the London Home Office’s civil servants, but none of them was prepared to accept the true meaning of the dangerous situation. Consul General Smallbones realized that it was necessary to first get the men released from the camps, into which they had been confined after 9 November, because without their breadwinners the women and children would not emigrate from Nazi Germany.

After the first unsuccessful exploratory talks in London, Consul General Smallbones contacted Sir Samuel Hoare, the Interior Minister, to whom he presented his plan. With a limited two year transit visa the threatened people would be brought to Great Britain where they would be on safe territory, while waiting for the country, which had issued them an entry visa for a future date. The Interior Minister accepted the proposal without calling for any parliamentary debate.

As soon as he returned to Frankfurt, Consul General Smallbones sought a meeting with the Nazi authorities. He reached an agreement with Frankfurt Gestapo, which led to the following arrangement: The family members would present to the British Consulate the documents relating to their already initiated emigration. Thereupon, they would receive a permit from the consulate, which would lead to the release of the interned Jewish men. The men would return to Frankfurt for a limited period of time, during which they had to report to the local police station on a weekly basis. Once they had sold their possessions and paid all the taxes and fees, which the Nazis required, they would be allowed to leave. The British Consulate verified if the already initiated emigration to the desired country was possible within two years. The consulate then issued a transit visa for Great Britain. Relatives or relief organizations had to provide a guarantee, which would serve as a financial security during the limited stay in Great Britain. All of the British consulates in Europe were soon working in line with the “Smallbones Scheme” and thanks to this scheme approximately 48.000 Jewish refugees were able to travel to Great Britain.

The massive efforts of Consul General Smallbones as well as the Quakers and the Cook sisters show that many people and their families would have been deported after 1941, had they not received help to emigrate in 1939.

See: www.sarachi.org/commemorating-diplomats.pdf See: Ambassador Henderson’s report about Hitler, Goering, Ribbentrop, London 1940, p. 28 See: Exibition Gegen den Strom: Editor: Fritz Backhaus/Monica Kingreen (Jewish Museum Frankfurt am Main). Catalogue, which accompanied the exhibition with the same name, Frankfurt am Main 2012