A Gestapo „Special Operation“ and Escape into Illegality

In autumn 1942 already – after the completion of the big deportations from Frankfurt am Main – the Hessian “Gauleiter” Jakob Sprenger instructed the head of the Gestapo to deport 100 “mixed persons first grade” and “Jewish mixed-marriage partners” per month to the concentration camps. Hessen-Nassau was to be reported as the first region “free of Jews”. No one within this persecuted group had reckoned on being deported, because officially the Nazi regime’s decision to proceed against “mixed marriage couples” and “half Jews” was technically only scheduled to start after the end of the war.

170 Frankfurt Jews who were identified as belonging to this group were deported in the first nine months after September 1942 (an unknown number from the Hessen-Nassau region was also deported). 28 of the persecuted committed suicide after receiving their summons. Many months went by before the news of this action –no hearing, only detention and deportation– was spread. In February 1943 Claire von Mettenheim noted this local action by the Frankfurt Gestapo and the fact that Jewish citizens were being deported to a camp in Upper Silesia without pretext from which none returned. Only a few relatives managed with great effort to get their partner released from Gestapo detention. Many people in “protected mixed marriages” trusted that their status would save them and therefore did not go into hiding upon receiving a summons.

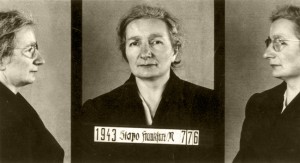

One of the few women to come out of prison was Jenny Iller. Her case shows how difficult it was to organize such a release. One of these women who were released later wrote, this was only successful by five from 80 women who were imprisoned.

Jenny Iller and her daughter Ruth received a Gestapo summons in March 1943. Ruth was classified as a “mixed person first grade” and the bishop of Limburg got involved on her behalf, so that she was released after three months. Ludwig Iller was not allowed to visit his wife in prison and only managed to remain in contact via secret messages hidden in the weekly laundry packages. Iller was severely insulted and threatened by the Gestapo civil servant Heinrich Baab. With the help of the prison doctor Dr. Vorschütz and the prison warden Liesel Wetzel he was none-the-less able to have his wife transferred to the infirmary for Jews, located at Hermesweg 5/7. A good dose of medical poisoning was sufficient reason to get her out of the prison. Jenny Illner escaped from the infirmary on Hermesweg after a few days. Her husband had had enough time to organize her life in the underground –sometimes it was for a few days, sometimes for months that she spent with families in Frankfurt who were prepared to help. The prison warden Liesel Wetzel belonged to this group, as did five families in Frankfurt, Wiesbaden, Offenbach, and in Rück, not far from Obernburg. It was there that she experienced the liberation by the Americans.

See: Petra Bonavita: Mit falschem Pass und Zyankali, Stuttgart 2009, pages 118-119 and in: Heike Drummer – Gegen den Strom, Editor: Fritz Backhaus/Monica Kingreen, compendium to the exhibit with the same title, Frankfurt/Main 2012, pages 50-52; see also Lili Scholz’s release from detention in: Lili Hahn, “… bis alles in Scherben fällt”, Cologne 1979.