The Quakers, who helped many of the persecuted, had to accept that they were unable to prevent some of their own members from being deported. If a visa application was not filed in time or lacked a sufficient affidavit, the political blockade regarding the visa limitations was unavoidable. There were too many difficulties during the preparation to escape to a safe foreign country.

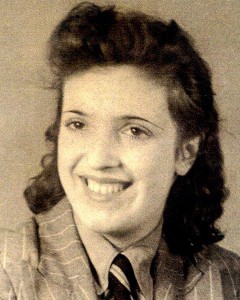

The Wiesbaden couple Dr. Erich and Elli Frankl got to know the Frankfurt Quakers during the 1930’s. They visited the latter’s Sunday prayer sessions and found “true” friends at a time when many old acquaintances distanced themselves. As they had not filed their visa application early enough, the involvement of the Quaker friends to escape Nazi Germany was hopeless. However, their two children Hai (actual name: Heinrich) and Hermine were able to get out in time. The 17-year-old Hermine reached England on 7 August 1939 via a children transport. The correspondence with her parents was difficult, because once the war broke out all letters had to be sent via relatives and the Quakers, which could take months. That is why Hermine confided her homesickness and longing to see her parents to her diary.

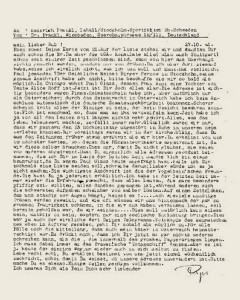

Hai Frankl was 19 years old. He had been forced to quit school in Wiesbaden and was only able to complete a gardener training position in a Jewish firm. On 26 August 1939 he entered Sweden with a transit via, which had been arranged for him with the help of Emilia Fogelklou, a Swedish author and Quaker, and friends from the Wiesbaden-Nerother Wandervogel Movement. He was placed in an agricultural company near Stockholm. The Quakers also tried to rescue the Frankl parents from Wiesbaden. Emilia Fogelklou and the Frankfurt Quaker Dr. Rudolf Schlosser made every effort to arrange a departure until the end of 1942. Letters went back and forth between Stockholm and Wiesbaden almost on a daily basis. The Quakers’ emotional assistance was a pillar of support in the months prior to deportation. Erich and Elli Frankl were deported to a camp on 10 June 1942 and subsequently killed.

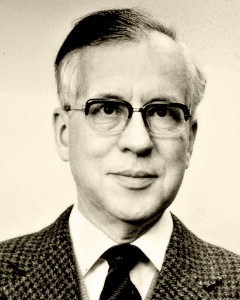

The daughter Hermine Frankl emigrated to the USA in 1945, married and had two sons with husband Gus. She died in Miami, Florida in 1987. Hai Frankl took his enthusiasm for music, which he had acquired in his parents’ house, with him to Sweden. He met his wife Topsy while studying decorative painting, which was financed by the Quakers. The couple traveled through German speaking Europe and performed folk music. Hai Frankl lived in Stockholm where he died on 13 January 2016.

See: Michaela Bolland: Wir sind noch! – Documentation Dr. Erich und Elli Frankl 1880-1942, in the municipal archives Wiesbaden; the posthumous correspondence is located in the Aktives Museum Spiegelgasse, Wiesbaden.

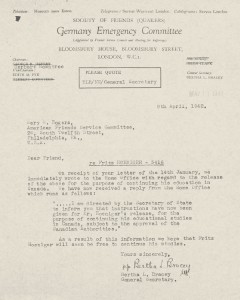

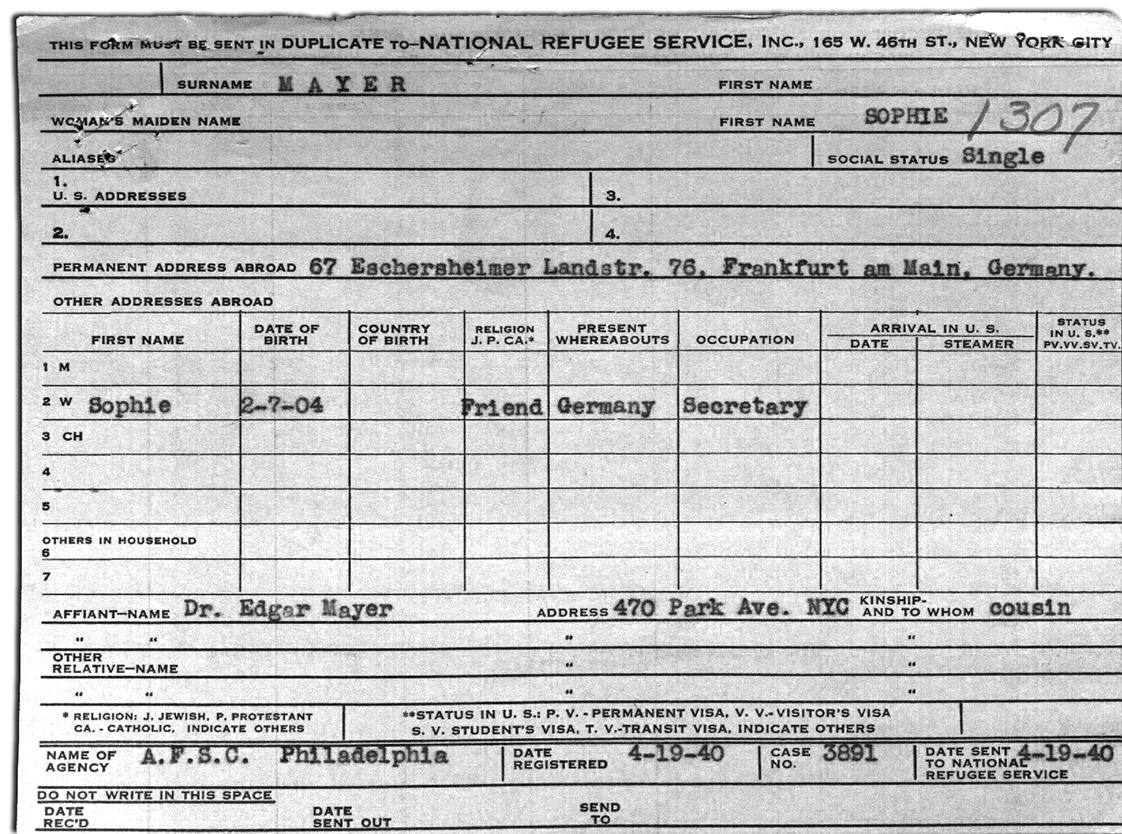

Sophie Mayer was a “valued member” of the Frankfurt Quakers. She lost her job as a secretary when her Jewish employer emigrated. After that she was active in the field of Jewish Welfare Care. She had taken care of filing her visa application and affidavit for the USA in time. However, when the American consulate in Stuttgart started to process her visa, the affidavit, which had been provided by her cousin in New York was no longer valid. The Frankfurt Quaker Dr. Rudolf Schlosser asked the American Quakers for help. The new affidavit arrived too late. When Sophie Mayer was forced to wear the yellow star she was no longer allowed to attend the prayer sessions and meetings. The Quaker Eva Hermann came to her apartment when it was dark. Sophie Mayer was deported on 1 March 1943 and murdered.

It was a stroke of luck that 17-year-old Fritz Höniger was on a farm training program in southern England while waiting to study in Birmingham. He had attended the international Quaker school “Eerde” in Ommen for two years and the Quakers wanted to support his further training with a scholarship. All these plans were destroyed after 9 November 1938, but his stay in southern England made it easier to arrange his family’s escape from Frankfurt. With the help of British Quakers he received a guarantee for his father, which confirmed the latter’s temporary stay for one year until Dr. Georg Höniger was able to emigrate to the USA in August 1940 with a visa which he had previously applied for. The family found a clergyman who was prepared to accept his 14-year-old sister Ruth. She left with one of the children transports. Only his stepmother, who was separated from his father for some time, did not file an application for a visa and had to stay in Nazi Germany. Elisabeth Höniger was deported in 1943 and murdered.

The Hönigers survived in three countries: The father Georg in the USA, Fritz as an “enemy alien” in a camp in Canada and Ruth in England. They were only able to reunite at the end of the war. The British Quaker Bertha Bracey got Fritz released (later: F. David Hoeniger) from the camp in Canada..

Siehe: Petra Bonavita: Quäker als Retter ... im Frankfurt am Main der NS-Zeit, Stuttgart 2014, S.210, S. 259-267