The contact between the “Aryan” Germans on the one hand and the Jewish Germans on the other hand became ever more dangerous after the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 came into effect, and was persecuted as “preferential treatment for Jews”. Friendly interaction with Jews, the transfer of food, advice and deeds connected with leaving the country could be interpreted in a mean-spirited way as “anti-social behavior” and could lead to questioning and imprisonment and in later years could even end in the concentration camp Ravensbrück for “Aryan” women or in the camp Dachau for “Aryan” men. The ghettoization of Frankfurt Jews in the Ostend neighborhood made it difficult to maintain the former neighborly contacts. One met secretly when it was dark and in remote spots. The start of the war and the introduction of food ration coupons resulted in critical shortages for Jewish households. After a few months the food ration coupons were marked with a “J”, which meant less rations and permitted shopping in only very few jewish stores. For example, coal was one of the limited items and was only delivered at the end of the heating period when the “Aryan” households had been taken care of, i.e. much too late for the Jewish households. The politics of hunger of the Hessian “Gauleitung” (regional leaders) ensured that the limited food supplies were too little to live on and too much to die.

Contrary to the commonly held opinion that there was indifference as to the fate of the Jewish neighbors and friends, there are countless examples of neighbors and friends helping to obtain food supplies. Anyone who was prepared to oppose the measures of the “Gauleitung” had to use imagination and energy so that humanitarian aid would not give the “National Socialists” a chance to denounce. Since the introduction of the infamous yellow star in September 1941 – sewn chest high onto clothing – greetings between neighbors with and without the star, let alone the transfer of food supplies, were dangerous.

Hermine Baumeister, together with her daughter and husband, went at night from their home on Frankenallee to bring food supplies to the senior cantor’s family, the Saretzkis. They walked the entire way in order to avoid attracting the attention of the conductor on the tram who would have noticed the regular nightly trips.

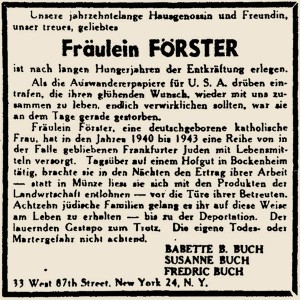

Gretel Förster supplied 18 families with food between 1940-1943. She worked on an estate in Bockenheim and instead of taking her pay in cash she delivered the “profit from her work” at night to the doorsteps of the affected. Patients gave unused ration coupons to Dr. and Mrs. Kahl, who in turn sent their son with very full baskets from Bockenheim to Ostend. Children aroused less attention than adults. Margarete Stock wrote about the procurement of food supplies by “proper Germans” for their Jewish friends, that although there was “no fat, meat, butter, vegetables, fruit, etc. for these poor people” everything possible was done for them. The Gestapo noted in detail in 1941 that there were approx. 100 “German blooded” household helpers working for Jewish families. The women who had been working there for decades did not want to leave their employers.

There was a great readiness to denounce such food supplies transfers. Walter Gottmann, who worked at the Department of Nutrition issued ration coupons without the imprinted “J” to his jewish acquaintance Max Prager. This was not allowed after Prager’s non-Jewish wife died. The action was denounced and Prager committed suicide on 12 January 1942 in order to avoid being sent to prison and deported. The employee Walter Gottmann was arrested ten days later because of “friendly relations with a Jew”, transferred to the concentration camp Dachau, where he died on 1 June 1942.

Karl Wischmann did not stop cutting Jewish customers’ hair. He was arrested in June 1942 and died in the concentration camp Groß-Rosen a few months later. The barber Karl von Walter survived the concentration camp in Dachau to which he had been sent for “favoritism to Jews”.

Otto Drews, a guard who worked in the Preungesheim prison, brought out letters from Jewish prisoners and brought in food supplies. He was sentenced to prison for 2½ years and died soon after his release.

Frieda Rodiger knew Josef Stern since 1931 and helped him out with food supplies and cigarettes. She was observed doing so on 19 January 1942. After being held for three months while awaiting trial she was sentenced to 15 months in the concentration camp Ravensbrück. She survived. Josef Stern was transferred to the concentration camp Dachau, where he committed suicide on 3 August 1942.

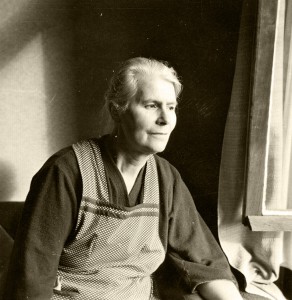

Else Epstein had established the “Bund für Volksbildung” (Federation for Adult Education) with her late husband Wilhelm Epstein. She supplied her Jewish brother-in-law Dr. Richard Löwenthal and did not allow herself to be prevented from continuing to meet her Jewish friends. A three-week prison sentence did not intimidate her, and in 1942 she was sent to the concentration camp Ravensbrück for eight months. She left Frankfurt after her release in order to avoid being persecuted by the Gestapo. She did not return to Frankfurt until 1945.

Martin Bertram operated a bakery at Rohrbachstrasse 58 since 1922. In 1933 he refused to hang up the sign “German Business”, which prohibited Jews from buying bread in his store. He was forced to give up his business in 1935. In 1936 he was sent to a concentration camp until the end of the war, because he was a Jehovah Witness.

On 19 January 1942 a customer observed that Theodor Schmidt, the owner of a fish store, gave two fishes as a present to the jew Josef Stern. The men had known one another for years. The eager customer followed Josef Stern from Schweizer Strasse to the clock tower at Sandweg. Once there he spoke to two policemen and denounced Josef Stern, who was arrested and shortly thereafter deported to a concentration camp. Theodor Schmidt was sentenced to three months in prison and according to his wife died two years later from the consequences thereof.

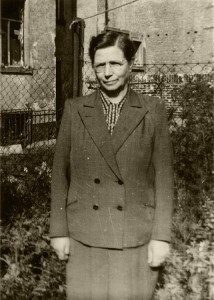

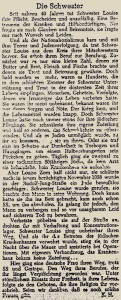

The nurse Luise Zorn met in dark archways and house entrances in order to give half starved people a small package. She climbed over the wall of the Jewish hospital at night and brought her own bandages and assisted during operations.

The supply of food was further limited at the end of 1942. There were less than 1000 Jews in Frankfurt after the conclusion of the large deportations (Jewish “mixed” spouses”, persons who were qualified as Jews, Jews with foreign nationalities and those employees who were engaged with winding up the Jewish Community. For them the already reduced rations were reduced even further. No meat, eggs, milk and bread ration cards.

Tilly Cahn wrote in her diary about the little bit which she was able to distribute in November 1941: “A large part of my daily work involves obtaining potatoes (very often as part of an exchange deal) and to bring these to them.” In February 1942 she commented: “misery wherever one looks.”

Theodor Hume ran an orthopedic supply store and was one of the last permitted to service his Jewish clients. He tried to comfort the complaining hungry customers with the comment “nothing sticks to the bones”. After that he bought a hundredweight of potatoes. The 35-year- old man was denounced in 1944 because of his anti-Nazi behavior; he died three months later.

Herbert Buchhold was familiar with the shortage of provisions. He worked at the large grocery store Schade & Füllgrabe on Hanauer Landstrasse. According to the Nazi racial laws he was categorized as a Grade 1 mixed blood and should have held back in order not to become a target. Herbert Buchhold was also denounced by an ardent Nazi because he gave groceries and damaged goods to Jews. He was arrested on 5 March 1943 and sent to the concentration camp Auschwitz-Monowitz. He was 23 years old at the time and he survived.

See: Dokumente zur Geschichte der Frankfurter Juden 1933-1945, Editor: Kommission zur Erforschung der Geschichte der Frankfurter Juden, Frankfurt am Main 1963, Pages 442-455. With regard to “Favoritism of Jews” see also the women from Frankfurt am Main who were deported to the concentration camp Ravensbrück: amongst others Else Foshag, Maria Lang, Anna Rodiger, Anna Strebe, Else Schneider, Gladys Schulz, in: Studienkreis Deutscher Widerstand 1933-1945, Frankfurt am Main KZ Ravensbrück, Lebensspuren verfolgter Frauen, 2009.