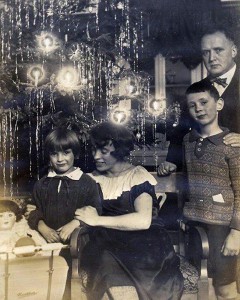

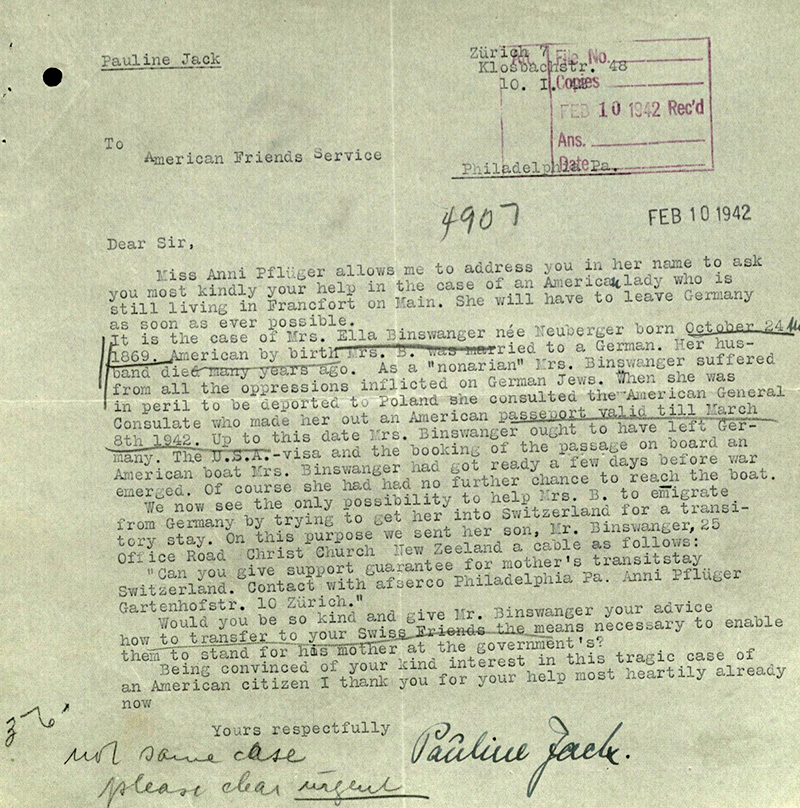

Her sister Pauline Jack was a music teacher. Her circle of contacts encompassed the world of opera and classical music and reached far beyond Frankfurt. The two English music enthusiasts Ida and Louise Cook, who scraped together every penny they could in order to follow their opera stars and the newest productions across the continent, were welcomed weekend guests in Arndtstrasse. The Blum daughters, together with the Cook sisters, were able to realize the very last possibilities for relatives and friends to get out of Nazi Germany. Pauline Jack compiled a list of people who had to desperately emigrate. Ida and Louise made their home available for “the interviews” with those people seeking help. Louise learned German in order to better understand these people. Ida Cook’s apartment in Dolphin Square in London became the first place of refuge for the refugees.

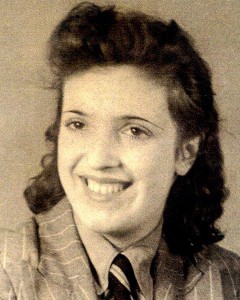

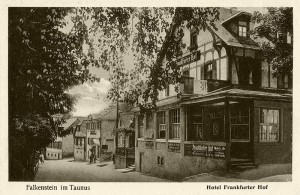

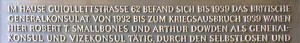

In 1935 Ida and Louise found out for the first time what it meant to be a German Jew in Frankfurt from their friend Mitia. In 1937 they helped the first of their friends to emigrate, amongst whom was Mitias’s daughter Elsa Mayer-Lismann. On 10 November 1938 Ida Cook witnessed the pogrom in Frankfurt. Her report about how the British consulate general opened his doors to the persecuted and the vice-consul general Arthur Dowden drove through the streets in order to distribute food, were quoted in the speech honoring the British diplomats in London in 2008.

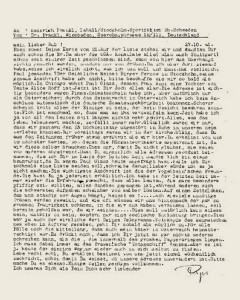

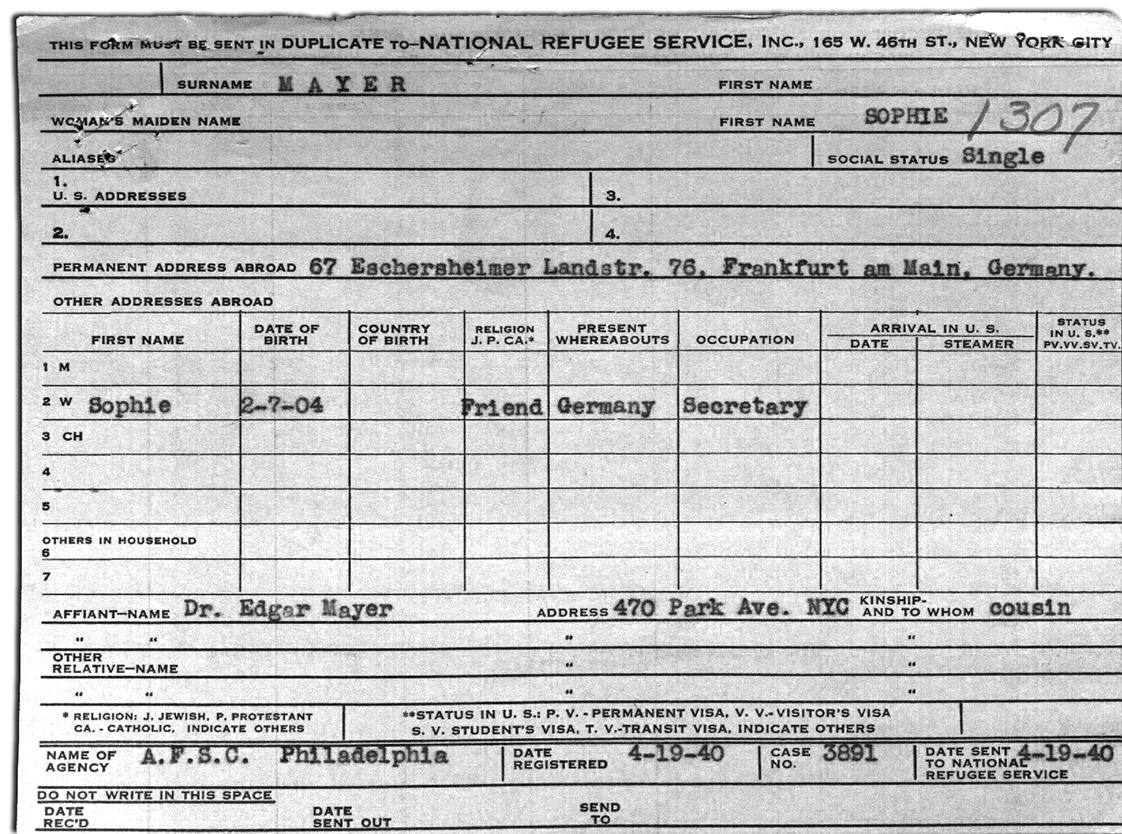

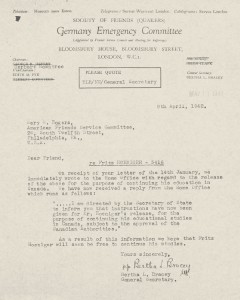

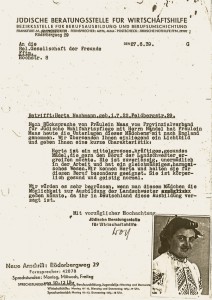

In 1939 Ida and Louise Cook proceeded systematically. They flew in from Croydon airport in London to Frankfurt on Friday evening in order to return on Sunday evening via ship, fully loaded down with furs and fancy clothes, jewel-studded broaches and money. The “presents” were intended to ensure the refugees’ subsequent survival in England. Ida and Louise held preparatory conversations with all those seeking help. They did not want to reject anyone. A seemingly complicated case very often proved solvable or a simple case turned out be insurmountable. The close contact to the British consulate made it easier for the English women to handle with individual cases. They reviewed documents in advance and established a convincing story in order to convince the consulate general to issue a visa. After they were successful in getting Elsa Mayer-Lismann out of the country, they helped her friend Friedl Bamberger and subsequently her parents, the teacher Lulu Cossmann, Lisa Basch from Offenbach, Irma Bauer from Vienna and many others.

Ida and Louise Cook were honored in Yad Vashem in 1964 as “Righteous Amongst the Nations” for 29 confirmed rescue cases. They received the “Heroes of the Holocaust Award” in London. Gertrud Roesler-Ehrhardt was awarded the Federal Cross of Merit in 1983 and the Johanna Kirchner Medal from the town of Frankfurt am Main in 1991. She died at age 96 in Frankfurt am Main.

See: Louise Carpenter: Ida & Louise – wie zwei Schwestern die Gestapo überlisteten, Zürich 2010; Ida Cook: “Safe Passage” – The Remarkable True Story of Two Sisters who rescued Jews from the Nazis”, Don Mills, Ontario, Canada 2008 About Gertrud Roesler-Ehrhardt and Arndtstrasse 51 The HR documentary film “Unter Denkmalschutz”, Eberhard Fechner, 1975, and Petra Bonavita: Nie aufgeflogen, Berlin 2013, Page 29 about the failed rescue of Karl Herxheimer. Internet: Links to Ida Cook, Dolphin Square in London, Elsa Mayer-Lismann and Friedl Bamberger.