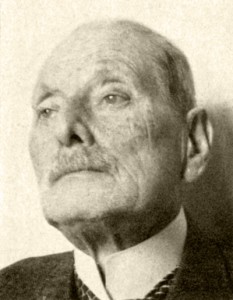

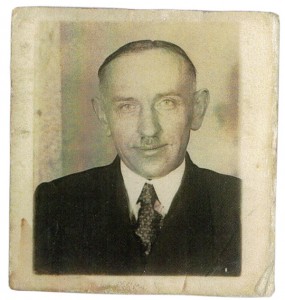

Christian Fries was a civil servant criminal investigator. He led a resistance group within the Frankfurt police headquarters and prepared the escape of the highly regarded Frankfurt professor Karl Herxheimer and his housekeeper Henriette Rosenthal to Switzerland. The impulse came from Gustav Weigel, who also belonged to Herxheimer’s circle of friends and supporters. The third helper was Gotthold Fengler, a Gestapo civil servant. The three helpers knew each other very well: they were friendly and familiar with one another as colleagues and were prepared to resist the Nazis.

Many friends had pleaded with Herxheimer for years to move to Switzerland as he owned a vacation house in Gunten am See. But why should he emigrate when even the tram conductor greeted him with the following words: “Nothing will happen to you, every child knows you and you’ve done a lot of good things for our city. You can’t go.” This confirmed the sense of home and his ties to the city. Soon however, Herxheimer was not allowed to enter “his” dermatology institute, and the generous benefactor who had helped found the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University was officially cut off. His large circle of acquaintances was all that remained. Former students, assistants and patients visited him secretly and brought him groceries. One of Herxheimer’s former assistants remembered after 1945 that there were enough courageous people who took care of him.

It was no longer a matter of care when one deportation followed another in spring 1942. Herxheimer’s friends were afraid for his safety. That is why Gustav Weigel together with the professor and the civil servant criminal investigator Christian Fries organized a secret meeting at “Oberschweinstiege” (in the Frankfurt “Stadtwald”). Weigel was a very good friend of the Gestapo civil servant Gotthold Fengler, who in turn was one of Christian Fries’ former colleagues. The most suitable location for these secret meetings during the summer was Weigel’s garden allotment on “Sachsenhäuser Berg”. Weigel was later counted as one of the members of Fries’ resistance group.

The organizational details of the escape were quickly discussed. Fengler obtained the fake passports for Professor Herxheimer and his housekeeper Henriette Rosenthal. Fries removed their “identity cards” including the passport lock in the police headquarters. Fengler wanted to borrow a car in order to bring the two elderly people to the border. Professor Ferdinand Blum, one of Herxheimer’s former university colleagues who had already emigrated waited for them on the Swiss side. His daughter Gertrud Roesler-Ehrhardt who lived in Frankfurt, was also informed of the plan. Unfortunately, the plan failed as a result of one small, unforeseen incident. Henriette Rosenthal was on her way to the post office because she wanted to send a small package to her “half Aryan” grandson. This was observed and reported by a member of the Nazi party. Rosenthal was arrested and only released shortly before being deported, so that she could pack her suitcase before being sent to Theresienstadt. As a result, the escape attempt failed.

The civil servant criminal investigator Christian Fries wrote about this failed rescue after 1945 in a long justification-paper of his own anti-Nazi behavior and his illegal resistance activities as a leader of a resistance group within the Frankfurt police headquarters. This group was part of the Wilhelm-Leuschner circle. However, all references to Fries and Fengler, which provided confirmation of the civilian resistance-circle were deleted from the tribunal files in 1947/48. At the same time Emil Henk’s publication of “The Tragedy of 20 July 1944” in 1946 lists case after case in which Christian Fries is mentioned in his capacity as “Stützpunktleiter” (leader of a resistance group). Christian Fries’ justification-paper, which he sent to his “dear friend Jakob Steffan” (a fellow conspirator within the Wilhelm-Leuschner circle), gives an insight into his resistance activities. He had checked forty people on account of their anti-Nazi attitude and their readiness to become actively involved in the event that the Hitler regime was successfully toppled. Gustav Weigel belonged to this group. In 1958 Christian Fries wrote that the Gestapo civil servant Gotthold Fengler had “rendered the resistance group valuable services when he, amongst other things, informed them in a timely manner about planned transfers of Jews, so that we could warn a number of those endangered”.

See: Petra Bonavita: Nie aufgeflogen, Gotthold Fengler: Ein Gestapo-Beamter als Informant einer Widerstandszelle im Frankfurter Polizeipräsidium, Berlin 2013; see also: Rechtfertigungsschrift Christian Fries in the Wiesbaden Stadtarchiv NL 75, Br. 1555; „Die Untoten“ about networks of civil resistance in: Der Spiegel Nr. 30/2015, pages 117-121