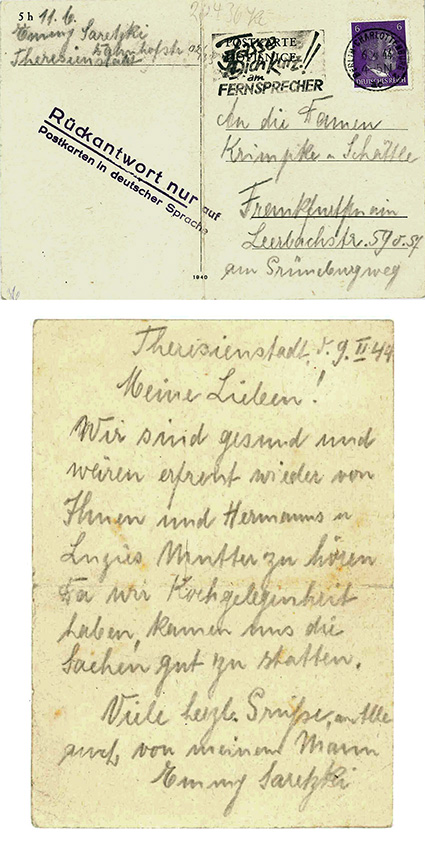

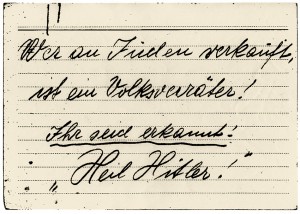

The contact between some Jewish and non-Jewish neighbors was so close that one asks: Could not the friends do anything to save them in Frankfurt? It was however fear, which prevented even the best friends from offering any help. The controls were so tight (neighborhood watches, local groups, 100% Nazis as neighbors) and the readiness to denounce others so great that even the thought of helping seemed hopeless. Therefore the non-Jewish friends watched hopelessly as the deportations took place. As Margarete Stock wrote to Julius and Emma Hess’ sons in Israel after 1945: “It was to date the most difficult thing in my life which could have affected me when your dear parents and many dear acquaintances left us”. None-the-less, the one thing which could be done to help Jewish friends survive in the ghetto and “keep their head above water” was to provide the deported with groceries and money until hopefully the end of the war. Packages however had to be disguised when they were sent and secret messages confirming receipt were sent back. Such contact seemed less dangerous for non-Jewish friends when “mixed marriage couples” or “half-Jews” who had lived in Frankfurt since 1943 acted as intermediaries. Numerous Frankfurt residents made use of this precautionary measure. That is why Georg Hartmann, the owner of the Bauer’sche Gießerei, slipped 100 Marks into the hand of one of his apprentices with the request that the latter’s father the lawyer Max L. Cahn transfer this amount to friends in the Lodz ghetto. Emmy Saretzki requested in a postcard sent from the Theresienstadt ghetto that her “half Jewish” friend Eugenia Schöttle pass on a message to the non-Jewish family Baumeister.

One had to assume the worst when no postcard confirming receipt of the survival package was received. The certainty of a friend’s death in the ghetto could only be confirmed after the end of the war. Wilhelm Wagner wrote that the small packages might have made survival possible, “if it were not for the unrelenting brutality of the inhuman Nazis along with the ‘final solution’ in the Auschwitz crematoriums which had otherwise determined our friends’ fate”..

“I have his name inscribed in Yad Vashem” ….

…. bequeathed Ernst Valfer about Josef Stumpf. In 1932 Josef Stumpf was 25 years old when he moved out of his parent’s house and moved in with the Valfer family who lived at Gutleutstrasse 95. At that time the Jewish couple Valfer owned the “Kellerei Germania” and a vineyard in Hochheim. By 1938 the Jewish couple had lost all of their properties through the “aryanization”. This theft troubled Josef Stumpf because he had been their rental tenant. He was a technical worker from profession and had been assigned to work on the construction of the Siegfried-Line, but he continued to visit the family on weekends even after he had moved away. This was no obstacle for him, even later on, when contact with the family became ever more difficult. The Valfers’ son Ernst referred to the fact that the trusting and close relationship continued even in dangerous times: “Stumpf put on the table (documents), and if anybody had found out that he leaves his top secret maps in the house of a Jew with his pistol on top of it they would have caught him right there and then.”

In March 1938 the couple sent their son Ernst with one of the children transports to France. In 1939, as their financial situation in Frankfurt worsened, Heinrich Valfer was hired as an office worker in the Stumpf family’s business — this alone carried with it a big risk because the employment of Jews was explicitly forbidden. All of the couple’s attempts to emigrate failed and on 19 October 1941 Heinrich and Frieda Valfer were deported to the ghetto in Lodz. In June 1941 their son Ernst was able to escape with one of the last children transports from France to the USA via Portugal.

He returned to Frankfurt as an American soldier and searched for the family’s friend. Although Josef Stumpf had tried to ease the couple’s suffering by sending money to them in the ghetto he was unsuccessful. The couple was murdered at an unknown location on an unknown date. Josef Stumpf showed Ernst the money transfer slips and the confirmations which Ernst’s mother had sent until such time as no more answers came. “This act of solidarity remained despite its immense meaning simultaneously meaningless: no one was rescued” Ernst Valfer wrote. Josef Stumpf belonged to the “five percent that took on danger for humanity”.

See: Interview with Ernest Valfer in: US Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington D.C.; with regard to Valfer see also: Benjamin Ortmeyer: Berichte gegen das Vergessen und Verdrängen, Alfter 1994, pages 39/40.

Packages into the Ghetto Theresienstadt

Wilhelm Wagner Sr. owned a leather workshop in Bergen-Enkheim, which is close to Frankfurt. He bought his linings from the textile merchant Elias Singer. The business relationship developed into a friendship, which was not severed during the Nazi period. Wilhelm Wagner Jr. grew up with his father’s friends.

When Elias Singer was forced to give up his business in 1938 the Wagners bought the remaining rolls of fabric, and when food supplies became scarce they helped the Singers to survive. The son Wilhelm risked a lot when in November 1938 he saved many prayer books, Torah scrolls and other irreplaceable cultural items from the synagogue on Friedberger Anlage and brought all of these items to the Singers’ home for safekeeping. The Wagners were unable to save Elias and Gella Singer from being deported on 15 September 1942. However, they did not remain inactive. They drove twice to the Singers’ home, which was located at Obermainanlage 12, in order to pick up the religious items from the synagogue and brought these to their own home where they were hidden in an iron-clad trunk. They also arranged to send their friends food packages to the ghetto in Theresienstadt so that they would not starve. Based on the mail and correspondence it is apparent that they had discussed this with their friends beforehand. One can only understand much of the coded text with the help of Wilhelm Wagner Jr.’s explanations, which he provided after 1945. This was necessary because the contact was per se “difficult and was accompanied with danger” and was only possible based on “clever disguised comments”.

Nine postcards, which were sent from Theresienstadt still exist. In order that no one could prove that there was any direct contact between the families Gella Singer wrote: “Our friends receive mail almost daily from their loved ones, which makes them very happy. Please convey our sincerest greetings to our loved ones and ask them to write, because we would be very happy to hear from them.” Wagner’s explanation: “Because of the danger of being charged by the Gestapo their receipt was only referred to in general phrases. – In order that we knew that both were still alive the sender was Elias Singer while the signature was that of his wife Gella Singer who had to have lived in another part of the confinement. – Shortly thereafter addressing mail directly was no longer possible because the local mailman (a Nazi activist) figured out what was going on and a continuation of the contact in this manner would have been suicidal.”

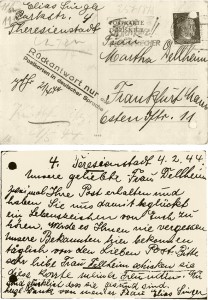

Other people who had been warned in this way would have stopped the mail correspondence and food supply packages, but Wilhelm Jr. found a solution for the food supply package problem. As of 1944 the recipient of the postcards from Theresienstadt was Martha Dellheim and Wilhelm Wagner left the following explanation: “After several attempts to make contact with the Singer family in Theresienstadt (amongst which were some via Switzerland) it was possible to find a trustworthy and reliable broker of our signs of life and packages in the form of the Dellheim family in Frankfurt am Main. This circumstance was favored because Alfred Dellheim was Jewish but his wife was not. After that we no longer sent the packages, but rather Mr. or Mrs. Dellheim dropped them off at various post offices in Frankfurt/Main. The contents of the packages were such that the Singer family could have held out until the end of the war if it were not for the unrelenting brutality of the inhuman Nazis along with the ‘final solution’ in the Auschwitz crematoriums which had otherwise determined our friends’ fate”. – As can be seen by a seal imprint it was no longer possible to send a letter to Theresienstadt as of 1944, but only simple postcards. For reasons of prudence everything, which was sent was disguised with aliases, for the most part “Schmidt”. … This postcard dated 4 February 1944, checked on 21 April 1944 and received on 9 May 1944 shows how difficult and dangerous it had become in the meantime to send messages, let alone the harassment by stretching the delivery over three months. It was always necessary to find a new code, for example here: ‘Send this card to my girlfriend’ so that we know that both of our last packages had arrived there. The sender of the card is in this case Mrs. Singer, Wallstr. 60/8 ‘living’ while the previous card is from ‘Elias Singer, Parkstrasse 4’. The last words on the card: ‘We are happy that we are healthy. Thank you very much from my wife’ referred first to a disguised report about various air raids which we had reported in numerous postcards and secondly Mrs. Singer thanks for the referenced packages which had arrived safely.” The final comments from Wagner Jr. refer to a postcard, which Gella Singer had sent on 19 April 1944. It is the last direct news from their friends in Theresienstadt. “We had reported about the son’s birth but also written about the effects of the severe air raids on Frankfurt and the destruction of their house at Obermainanlage 12. Through the use of disguised comments we referred to the war’s forthcoming end, so that they would not lose courage. However, towards the end of November 1944, i.e. a few months prior to the liberation, both of them – according to a statement of the survivor Josef Kanner they were designated for ‘transport’ to Auschwitz where their fate was determined.”

Elias and Gella Singer were murdered in the extermination camp Auschwitz. Elias Singer was 59 years old and Gella 50 years old. In November 1945 Wilhelm Wagner brought the Hebrew Torah scrolls, many prayer books and other ritual items, which had been entrusted to him to the Frankfurt rabbi, Dr. Neuhaus..

See: Petra Bonavita: Mit falschen Pass und Zyankali, Stuttgart 2009, pages 103-108.

A valuable Ring was smuggled into the Ghetto Minsk

The neighbor and friend Margarete Stock remained in contact. She managed to send packages to the ghetto for two years via two guards from the ghetto who had returned on home leave to Frankfurt and respectively Giessen. Included in the packages were food supplies, clothing and also a present for the guards. Emma Hess wrote long letters in which she described her husband Julius’ death, her work in the sewing workshop and life in the ghetto. One day Emma Hess asked her friend to send a valuable ring, which she was not allowed to take with her when she was deported. “Well, that made me happy when she wrote that it was in her possession and she had been able to do a lot of business with it”, reported Margarete Stock to the sons after 1945, who in the meantime were living in Israel.

In hindsight she realized how reckless it had been to send the packages and was aware that she stood with one foot in ”the concentration camp”. Her husband had implored her finally to stop. She did it behind his back and was very lucky. The contact ended when no more letters from Emma Hess arrived in Frankfurt. She had died in an unknown location..

Research Renate Hebauf, Frankfurt/Main. See: Laying of the “Stolpersteine” for Julius and Emma Hess in 2010, Stolpersteine Initiative Frankfurt am Main.